Who Gets to Tells Your Story? Palestine, Congo, Miles Morales and Dignity in Storytelling

“Someone asked me today to describe how my life was before the aggression, and trust me I didn’t have an answer.. I didn’t know what to say.. I feel so speechless and I find it hard to remember my life before the aggression, the 28 days that passed feels like forever this aggression just reminds me of previous aggressions.. life was never normal in Gaza, but I miss what I thought was a “normal” life..”

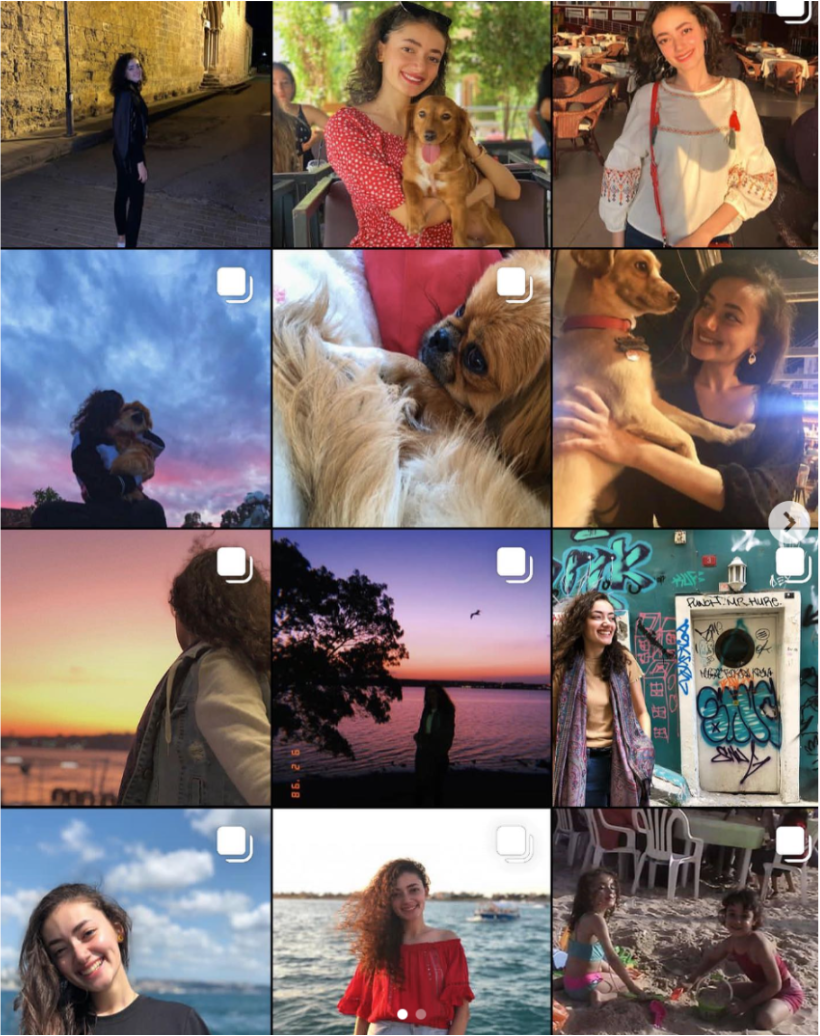

- Plestia (@byplestia on Instagram) who is one of the Palestinian journalists on Instagram sharing the day-to-day life now in Gaza.

Before becoming a storytelling evaluator at UBUNTU, I’ve always loved a good story. Books, TV shows, movies, social media, grown folks business I overheard in the kitchen - it didn’t matter. Reading dystopian heroism like The Hunger Games kept me fed, and morbidly engaged, as a high school student. And one of my favorite movies of the year, Spider-Man: Across the Spider Verse, has me rooting for Miles Morales no matter how naive he can be as a young Black man in the U.S.

But for the past month my social media feed has been filled with real-life stories of people raising awareness for Palestine, protests and calls for ceasefires, the Western media ignoring Palestinian narratives, politicians censuring the only Palestinian Congresswoman Rashida Tlaib, and live accounts from people like Plestia who are documenting their own genocide in 2023.

Did you read that last part well? In 2023, we are observing the genocide of Palestinians as “collateral damage” through Instagram, Tik Tok, Twitter, and all forms of media. In the palm of our hands we see death, we engage with death, and we carry death as our phones are made with cobalt mined by the Congolese people who too are being displaced in the name of imperialism, colonialism, and capitalism. And yet, I wonder how much of this I would, or would not, know if it wasn’t for social media and people like Plestia sharing their stories?

My foundational understanding of storytelling evaluation strategies, such as photovoice and journey mapping, were how they provide a holistic view and value the perspective of participants in an evaluation. We use photovoice to empower people from marginalized groups to capture and record their life experiences and community through photography as the focal point of an evaluation. Then, journey mapping is an art-based storytelling research method that provides participants with an opportunity to meaningfully capture key moments in their life on a timeline, defined by and explained by them. It’s meant to humanize what evaluations of the past have regulated to numbers and statistics.

Scrolling through Plestia’s feed is an example of both journey mapping and photovoice. You can see the moment her feed turned from a regular woman, finding the beauty in her everyday life in Gaza, to a journalist documenting the bombings and horror she’s now experiencing in what’s left of Gaza. Her captions and videos are firsthand accounts of the children she is meeting and her reflections on what’s happening in real-time. In fact, Plestia and many other Palestinians, such as Motaz and Bisan, are essentially the story collectors and participants conducting an evaluation against multinational, transatlantic governments, and western media who are refusing to share their stories as Palestinians - which is an evaluation that is unheard of at this magnitude.

Watching this unfold has caused me to reflect on my relationship with storytelling and who gets to be a storyteller. In Spider-Man: Across the Spider Verse, one of my favorite fictional hero stories, everyone is telling Miles how his story is supposed to go and who he is supposed to become. He learns his father, the police captain, will die as a “canon event” that happens to all Spider-Mans in order for them to reach their full potential. He’s even told that his father dying is “for the greater good.” But, in spite of it all, because he’s deemed the “hero,” the story is told from his perspective.

Which brings me back to Palestine and the Congo. Historically, the people with the least amount of power and money, and most amount of melanin, are never the heroes. They are often the aggressors, disruptors, and terrorists whose voices are silenced and deemed not worthy because of their nationality, ethnicity, race, religion, etc. They will not read history books telling their side of the story nor win awards for their own storytelling because, as it was put so plainly in Spider-Man, “that’s not how it works.”

Death of innocent people should not be a “canon event” or “collateral damage.” Yet we know that genocide is not new and it has been happening to Black, Brown, and Indigenous peoples for decades. From slavery to the Trail of Tears, what is happening to Palestinians has, can, and will continue to happen to those who do not align with imperialist and colonialist governments in the West. And those who do not get in line are the ones who do not get to tell their stories.

However, what is new is technology and the power of social media that turns Plestia into a storyteller. A phone allows for her to share daily updates that the news refuses to show. And a phone allows for people like me to learn what is happening on the other side of the world from her updates. But, despite being a powerful tool, those phones are also displacing and killing Congolese people whose stories we hear less about even on social media. So how is it that we can dignify ourselves as storytellers with the very devices that threaten the Congolese people's right to exist and thrive?

I do not have all the answers, but I do have empathy and know that Palestinians deserve to be free. I know that before I am a storyteller, evaluator or writer, I am a Black American woman born in the United States, a descendant of Africans who were enslaved, making us a stolen people on stolen land. There is history I will never know about my people, along with stories and connections that are lost forever. Because similar to Plestia, the Congolese people, and Palestinians around the world, we too have often been deemed unworthy. And even though I like to believe we are living a Miles Morales hero arc creating our own stories and adventures, that is not always the case when my tax dollars are being used to create bombs and fund genocide. Is this truly “just how it works?”

An African proverb says that “Until the lion tells the story, the hunter will always be the hero.” And though some days it feels like a pipe dream, my hope is that Plestia can one day return to her original Instagram feed. But honestly one of my biggest fears right now is opening my phone and reading that Plestia’s story has come to an end. So as we scroll, whether in pursuit of self-education, conversation, or merely to stay informed, I want us to ask who our likes, engagement, and shares are giving power to? How are we uplifting and dignifying real stories of struggle and perseverance of those most affected by issues and not just the fake dystopian ones we read in books? And what do we need to be doing now so that the stories of Plestia and the yet unheard stories of the Congolese people do not get erased? Because their trauma, death, cries, and sacrifice cannot simply be another canon event or collateral damage.

Because as evaluators, how do we even fathom “analyzing” these results?